26 Mar 2014

Intestacy 101

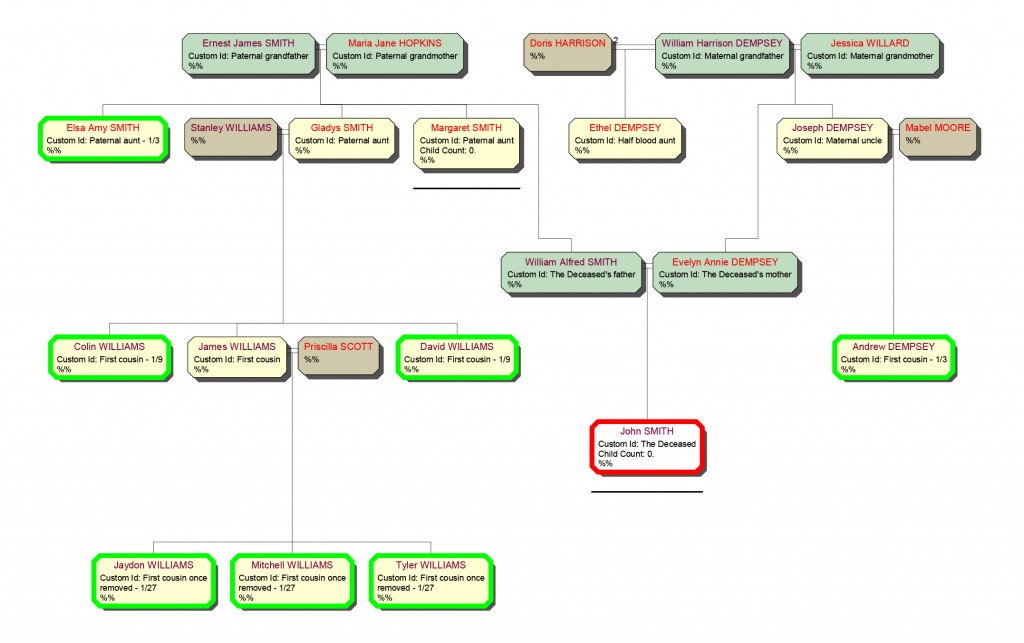

As a professional probate genealogist, I spend my working life dealing with complex intestacies. While no legal expert, I am often contacted by clients wanting to pick my brain and it occurred to me that a ‘back to basics’ article might be helpful. This article is intended really for those legal practitioners who only come across these kinds of estates once in a blue moon as a pared-back introduction to the nuts and bolts of estate distribution. By way of example, I’m going to look at the family tree of the late John Smith.

John Smith (Deceased)

Mr Smith died without leaving a Will. From the tree we can see that there are no heirs in the following prior classes of kin: 1) spouse or civil partner; 2) issue; 3) parent; 4) siblings of the whole blood and, where predeceased, their issue; 5) siblings of the half blood and, where predeceased, their issue; 6) grandparent. Accordingly, the next of kin are in the class of the uncles and aunts of the whole blood and, where predeceased, their issue.

Whole bloods and half bloods

Whole bloods have a prior claim to half bloods. The maternal grandfather William Harrison Dempsey remarried following the death of his first wife Jessica. The second marriage produced a daughter Ethel Dempsey who survives but, as an aunt of the half blood, Ethel is not entitled to share in the estate.

How far down the line does the inheritance pass?

Beneficial entitlement continues to pass down the family line until living heirs are identified. So even though there is a surviving aunt, the first cousins (children of a predeceasing uncle or aunt) still benefit. Where a first cousin predeceased, their children benefit. In the event that, for example, Mitchell Williams (the first cousin once removed) had predeceased, his share would pass down to his issue (if he had any).

Before you distribute

You need to be completely sure that there are no heirs in a prior class of kin. I’m bound to say that the best way to ensure this is to instruct a reputable firm of probate genealogists to verify the tree. However, there are cases where this is not really necessary.

In the Smith case, the Administrator is the elderly but ‘sharp as a tack’ paternal aunt Elsa Smith. Having known John Smith his entire life, she knows that he was an only child who lived with his parents until they died and remained in the family home thereafter until he died. Understandably, she does not wish to spend estate funds on genealogical research to prove this. This is fine, of course, as long as she is explicitly made aware, on the record, of her enduring potential personal liability should a prior claimant pop up in the future.

Incidentally, missing beneficiary insurance to cover claimants from the immediate family would only be available if independent verification had been undertaken to support Elsa’s testimony.

Distribution

Determining who gets what can look pretty daunting when you’re faced with a massive family tree (some of the trees we produce stretch to several meters). We supply a distribution schedule as standard with our completed family trees but if you have do it yourself, it’s actually very straightforward.

From the tree, we can see that John Smith had three paternal aunts and one maternal uncle. On the paternal side, the aunt Elsa Amy Smith survives; the aunt Gladys Williams predeceased leaving surviving issue; and the aunt Margaret Smith predeceased without issue. The maternal uncle Joseph Dempsey predeceased leaving one son.

Initially, the estate is divided by the number of uncles and aunts who either survive or leave surviving issue. I have seen more than a few instances where half is incorrectly paid out to the paternal family and half to the maternal family. In fact, the correct distribution ratios for this estate would look like this:

- Elsa Amy Smith receives 1/3 of the estate.

- Gladys Williams’ 1/3 is divided three ways: 1/9 to each of her surviving sons Colin and David, and 1/9 to the line of her son James who predeceased leaving issue.

- James Williams’ 1/9 is further divided three ways meaning that his sons Jaydon, Mitchell and Tyler receive 1/27

- The remaining 1/3 passes to the maternal uncle Joseph’s son Andrew Dempsey.

Tip 1

I find it easier to think of the shares as whole numbers rather than fractions. So, as an example, the ten surviving children of a predeceasing cousin entitled to 1/16 of the estate each get (16 x 10 = 160) 1/160 of the estate. This helps when the shares become extremely tiny such as the case I recently worked on where five brothers each received 1/2160 of the estate.

Tip 2

It would be pretty disastrous to make a mistake when calculating the fractions to which each heir is entitled. It’s a good idea, as a final check, to put your fractions into a spreadsheet and add them up. If they don’t add up to one someone has been missed out or is getting an incorrect proportion of the estate.

Conclusion

There’s nothing groundbreaking here but there might be something that you’ll find useful, particularly if your role doesn’t require you to tackle many of these types of cases. If you ever need to discuss a case, it may be worth calling a reputable genealogist. They are actively involved with these types of cases day in, day out so can help to ensure that what can seem at the outset a potentially complicated task is in fact a straightforward one.

Matthew Moore is the director of Moore Probate Research www.mprmissingheirs.co.uk

Email: matthew@mooreprobateresearch.co.uk

Tel: 01225 690 021